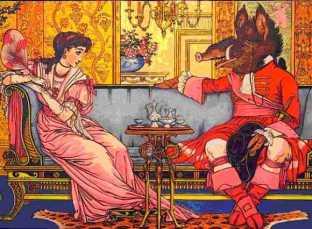

Beauty and the beast

Beauty and the beastA REAL TEST OF PRIVATE EQUITY.

TERRA FIRMA AND EMI

In 2007 we questioned whether private equity - an essentially value-extracting industry - could successfully manage a creative business, or for that matter any business requiring special skills or technologies.

At that time we said:

In a previous article, Private equity is a superior model of capitalism - some things to think about, we differentiated between venture capital and private equity. Venture capitalists invest in start-up enterprises or businesses at an early stage in their development which need capital to help them grow. They often develop close relationships with the enterprises that they support and get to know their businesses well. Private equity investors buy mature businesses, and extract value by use of some or all of the techniques below:

Private equity: how do they do it?

An excellent example is what a private equity consortium did when it bought the UK retailing chain Debenham's for nearly £2 billion, putting in £500 million of capital from its own investors and borrowing £1.4 million, then delisting the company from the London stock exchange:

- Property was sold off and leased back to realize £400 million.

- Borrowings were boosted dramatically from the £100 million when it was a public company, to £1.9 billion.

- Huge "special dividends," believed to be between £200-300 million, were paid to the new owners, reducing their personal capital risk exposure.

- The three most senior employed managers were incentivized by being given 10 per cent of the shares (fairly described as "potentially life-changing rewards").

- About £100 million of tax was saved by the shift to debt financing (as such interest costs are a fully deductible expense, reducing taxable income), and some financial engineering making use of offshore companies.

- Cash flow was boosted by a sharp cutback in capex.

- Creditors were made to wait longer for their money and customers' discounts were cut, reducing working capital costs.

- Stockturn was improved.

Guy Hands of Terra Firma capital is a well-known exponent of the latter form of investment. In the good times, which may be passing, Mr Hands and many of his cohorts have made huge amounts of money, using cheap borrowing to leverage their investments. Now that cheap money is drying up, it will be interesting to see how the new Masters of the Universe fare.

The controversy about private equity investors and their impact on businesses remains unresolved. We really do not know the answers to a number of key questions, for example:

- Does private equity generally add value to the companies that pass through their hands - or do they simply extract value, leaving companies in a less robust state for the longer term?

- Is the private equity 'treatment' more appropriate for certain types of business than others? For example, how does the private equity approach suit businesses that depend on high knowledge, high technology and complexity or high creativity?

- Is private equity investment really another form of asset stripping and leveraged buyouts as practiced by KKR, Hanson Trust and such as Slater Walker, Goldsmith et al and brilliantly described in 'Barbarians at the Gate'? If so, whilst their results seemed to be brilliant for a period, their performance subsequently languished for lack of investment and it became apparent that companies such as Hanson really destroyed long-term value.

Terra Firma and EMI - a good test case

The answers to these questions may become a little clearer through the case of EMI, which was bought by Terra Firma for £3.2 billion in summer 2007.

This is a particularly interesting case, because EMI is a business based on the creative output of artists, some of whom are brands in their own right and not beholden to the wishes of financiers, for whom they have a fine contempt. (Tim Clarke, manager of Robbie Williams described Hands as behaving like a 'plantation owner' who picked up EMI as a 'vanity purchase'). Additionally, a typical private equity strategy of leveraging the music publishing part of EMI, based on past repertoire and copyright material, by raising borrowings against the value of these assets appears to be blocked because of the credit crunch.Can private equity manage and develop businesses?

The future of EMI as one of Britain's last large creative companies is important, but how Terra Firma develops the business is even more significant, because it is a real test of whether the essentially financially driven, value extracting approach that is now dominant in larger public and privately financed companies can actually really create competitively sustainable enterprises. So far, it is more than clear that membership of the FTSE 100 is tantamount to the kiss of death for high-tech and innovation-led enterprises. There are virtually none left, having failed through a lack of investment and competitive stamina or by simply being sold to foreign buyers.

Now it's the turn of private equity to show what they can do. We should keep an eagle eye on what happens, maybe with the following questions in our minds:

- Will Terra Firma stick with the business or try to deal its way out of trouble?

- What will the artists do?

- What will happen to EMI's market shares?

- Can EMI develop new revenue streams?

- Are profit improvements a result of cost reduction or improvements in the top line revenues?

Amongst those who ought to join us in our vigil are the editorial staff of 'The Economist' which declared private equity to be 'a superior version of capitalism', Shadow Chancellor George Osborne, who asserted, "Private equity is a beacon of British excellence" and Gordon Brown, who seems to have followed Tony Blair in having a very favourable view of the industry and its benign impact on Britain.

Two investment banking friends are firmly of the belief that Hands will come to grief, as they think he has attributed success in benign market conditions to his own genius, and become arrogant and sloppy in his appraisal of acquisitions, believing that he can finagle his way out of any trouble. This time, they think he will fail.What do you think?

AND THE ANSWER IS........

Apparently revealed by the Observer newspaper of December 13 2009:

"Private equity group Terra Firma is looking to bring in outside investors to help prop up music company EMI, which is creaking under £2.6 billion of debt. EMI is profitable at the operating level but has been hit hard by borrowing costs that have forced Terra Firma to twice inject equity into the operation in the past 18 months. Hand's latest attempt to recapitalise EMI would involve Terra Firma and new investors injecting £1 billion of equity. But the plans could be contingent on him being able to persuade Citigroup to write off £1billion of debt.

"The EMI buyout has been a disaster for Terra Firma. "Efforts to cut costs at EMI have been met with a barrage of complaints from music acts, many of them complaining that Hands does not understand the business. Among those that have quit the label are Radiohead and the Rolling Stones. Hands has made swingeing cost cuts and axed 2000 jobs in a bid to boost profitability. But he admitted recently that buying EMI was one of his biggest mistakes and that if the auction had started just two weeks later - as the credit crisis began to unfold- he would not have gone ahead."

PRIVATE EQUITY INVESTORS - MASTERS OF THE UNIVERSE OR SIMPLY ASSET STRIPPERS?

It is becoming very clear that the modern private equity model, which essentially focuses on loading businesses with debt and extracting assets to earn high short-term profits (5 years is short term in a business of any complexity) for a small number of people by floating or selling the business is completely unsuited to high technology, knowledge-based or creative businesses.

The original model of venture capital, managed by people who had a "feel" for the businesses which they invested in, were willing to add expertise and stand by while the business grew has become massively distorted by the contemporary private equity business.

London - The Great Investment Disaster

Given the essentially short-term nature of the main investment markets and the gross speculation practised by Hedge Funds; the chances of science or technology business gaining access to understanding investors is fairly remote.

The London investment market is now dominated by:

- Large institutional investors, the majority of which churn their share portfolios to realise short-term gains and hope for takeover bids to boost their incomes

- Private equity, which is a value-extractive, not value-creating activity masked by secrecy as to the real results of highly leveraged asset stripping

- Hedge Funds, which make money primarily from instability in the markets and are not averse to causing it for short-term gain.

The result of this aversion to responsible long-term investment in existing or new science and technology businesses has been a disastrous decline in UK technology and manufacturing, failure to take advantage of the research base in universities, and missing the boat on green energy developments.

Even worse, the UK has become dependent on the finance sector, the cause of the problem in the first place, and now has a grossly unbalanced economy and a structurally permanent balance of trade deficit.

Is there hope of reform?

Most of the conditions exist for a revival of the UK economy - there is a strong wellspring of creativity a good university science base and a relatively well educated workforce. All that's missing is consistent long-term investment.

The initiative for change must come from government, which in addition to its own investment in strategic technologies like green energy must also create significant advantages for responsible long term investors that are willing to support technology and knowledge-based start-ups and help smaller companies to grow. Years ago, that was what 3i's was set up to do, but under City pressure that company abandoned investing in newer and smaller businesses a long time ago.

Britain will not escape from the deadly trap of total dependence on finance industries, consumer spending and housing and be able to build an intelligent and balanced economy without a massive stimulus.

From government.